A Perfectly Normal Company

The Erfurt company was founded in 1878 by master brewer Johann Andreas Topf (1816–1891) as a manufacturer of incineration facilities. Under his son Ludwig Topf (1863–1914), the company – now operating under the name J. A. Topf & Sons – grew to employ a staff of more than five hundred. Before World War I, J. A. Topf & Sons was already among the world’s leading manufacturers of malting facilities for breweries. Other areas of production included steam boilers, chimneys and grain stores, to which ventilation and exhaust systems and (from 1914) crematorium furnaces were soon added.

During the Weimar Republic, directors appointed by Ludwig Topf ran the company, which continued to expand. Nevertheless, the insolvency of Topf & Sons was only narrowly avoided in the global economic crisis of the early 1930s. Only when the German Reich launched its rearmament programmes in 1935 did the company’s sales recover.

Ludwig Topf was born in Erfurt in 1903 as the eldest son of Ludwig and Elsa Topf. After taking the "Abitur" school-leaving examination he enrolled at Hanover Technical College in the winter semester of 1922 to study mechanical engineering. His relationship with his mother, the owner of the company since the early death (in 1914) of Ludwig Topf, deteriorated increasingly. Although he came from a wealthy industrialist background, he was obliged to support his studies by seeking employment as a manual worker, private teacher, casual labourer and coal trimmer on an ocean steamer.

Between 1926 and 1931 Ludwig Topf studied in Berlin, Rostock and Leipzig, concentrating primarily on economics, sociology and law. He began a thesis on the subject of "Malt Production in Germany." In 1931 he joined the company as a salaried employee.

Ernst Wolfgang Topf, born in 1904, passed his school-leaving examination in 1922 and completed a commercial apprenticeship in Hanover. He went to Leipzig with his brother Ludwig and gained a commercial diploma there after four years at the trade institute. He also studied law as a secondary subject and was planning to gain a doctorate. In 1929 he changed his plans – the result of pressure from his mother – and joined the company, beginning work there as an ordinary employee.

At the end of April 1933, Ludwig and Ernst Wolfgang Topf became members of the Nazi Party. During the years that followed, they exerted an increasing amount of influence within the company. In 1935 Topf & Sons was converted to a "Kommanditgesellschaft" (limited partnership). The Topf brothers took over management of the company as fully liable partners.

Even before World War I, Topf & Sons was no longer a medium-sized company, its employees already numbering more than five hundred.

As part of company policy, the members of the staff were encouraged to remain with the family company by offers of social benefits such as pensions and residential accommodations as well as bonus payments. After 1933, the ideological and political elements of National Socialism were easily absorbed by the principle of the "company community." This transformation involved the designation of the Topf brothers as "works leaders" and membership in the German Workers' Front ("Deutsche Arbeitsfront," DAF). In 1939 the workforce reached its peak with a staff of 1,150. During the war this number was reduced by around half when many men were drafted into the army. They were replaced by prisoners of war and forced labourers.

Only the German employees counted as members of the company community. In the eyes of the company management, this community also included employees who had already suffered persecution – and sometimes even imprisonment – as members of the KPD (German Communist Party) or so-called "half-Jews."

After the economic depression of the early 1930s, it was primarily silo construction that brought in increased sales. During World War II, Topf & Sons also produced armaments, especially grenades, as well as spare parts for the "Heinkel 111," the standard bomber of the German Luftwaffe.

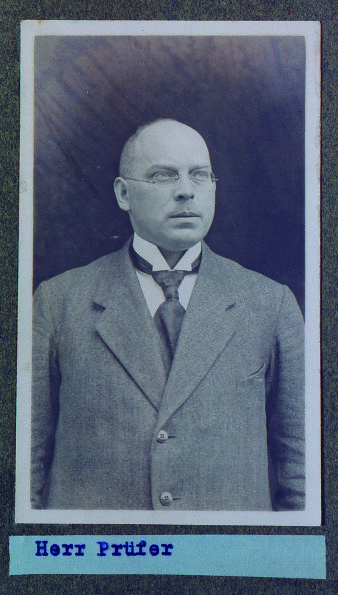

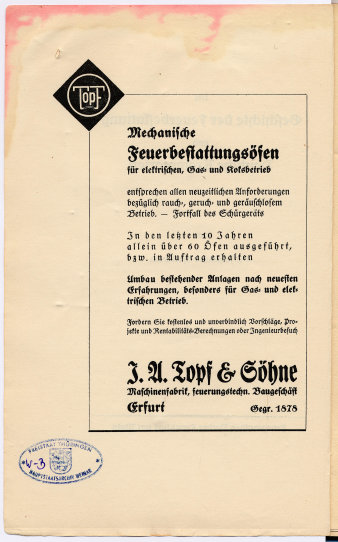

Department D for "Incineration Facilities Construction" had begun developing crematory furnaces in 1914. Topf & Sons soon succeeded in establishing itself as a leader in this new market. Nevertheless, the crematorium business accounted for only a small proportion of the company's total sales. In 1941, Department D IV for "Specialized Furnace Construction" was formed under the management of Kurt Prüfer, with exclusive responsibility for the construction of waste incinerators and crematory ovens.

Kurt Prüfer was born in 1891, the son of engine driver Hermann Prüfer. After secondary school, he was apprenticed to a bricklayer before studying structural engineering for six semesters in Erfurt. He joined J. A. Topf & Sons at the age of twenty and worked there for one year as an engineer before entering military service.

In the First World War Prüfer served on the Western front. Returning to Erfurt, he completed his studies in 1920 and again joined Topf & Sons, specializing in the construction of crematorium furnaces and playing a key role in the establishment of Topf & Sons' market leadership in this field.

Prüfer's contribution to the company's overall sales was modest. In his position as the engineer responsible for crematorium construction he was therefore able to earn only limited commissions to boost his salary. During the economic crisis of the early 1930s, he succeeded in averting his dismissal only by accepting enormous reductions in salary. Even after being appointed Senior Engineer in 1935, Prüfer was never awarded commercial power of attorney ("Prokura"), and thus held no authority to sign documents, remaining dependent on his superiors for the conclusion of business transactions.

In April 1933 Prüfer joined the NSDAP along with the Topf brothers. When the SS began to install crematoria in its camps in 1939, Prüfer saw an opportunity to enhance both his reputation and his income.

The first German crematorium commenced operations in Gotha in November 1878. By 1914, no more than twenty further crematoria had been constructed.

The first cremation adherents, known as "Crematists," came from the middle classes and formed societies calling for cremation of bodies as an appropriate contemporary form of burial. Opponents of the movement decried their views as irreverent and un-Christian.

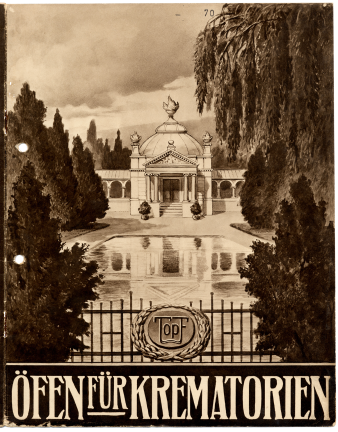

To increase the popularity of cremation, the Crematists introduced elements of the traditional funeral culture into the cremation process. Crematorium architecture was reminiscent of churches and temples to add a sacred note to the cremation service, while the technical facilities were concealed in the basement of the building.

After World War I, the lower costs of cremation led to an increase in the popularity of the method, particularly among the urban working class. It was not until 1934 that legislation was passed which applied nationwide and confirmed the equal status of cremation and inhumation. In this regard, Topf & Sons recommended itself as a producer of crematorium technology that allowed an especially dignified incineration (cf. Fig. 13). As the engineer responsible, Kurt Prüfer emphasized that "cremation [must not be allowed to] sink to the same level as carcass incineration, but [must] primarily consider aspects of hygiene and reverence."

After decades of discussion, the Cremation Act standardized the regulations previously applying in the various German states. The Act still applies in some German states today.

Cremation Act of 1934, Art. 2, Paragraph 1

The type of funeral shall be in accordance with the will of the deceased.

Cremation Act of 1934, Art. 8, Paragraph 1

Approval for the construction of a crematorium may only be issued to municipalities, intermunicipal associations and such corporations under public law having responsibility for the procurement of public places of burial. When approval is issued, care must be taken that the crematorium is designed to uphold the principles of dignity.

Cremation Act of 1934, Art. 3, Paragraph 2

Approval [of cremation] shall only be given on submission of

1. the official death certificate;

2. certification by a public health officer issued after examination of the body, specifying the cause of death and confirming the absence of suspicion that death was due to unnatural causes.

Rules of Operation for Crematoria, November 5, 1935, Art. 5, Paragraph 3

Measures must be taken to ensure that the cremation upholds the principles of dignity.

Rules of Operation for Crematoria, November 5, 1935, Art. 5, Paragraph 6

During the cremation process, measures must be taken to ensure that no smoke is emitted from the chimney if possible. Intervention of any kind to accelerate the process is strictly prohibited.

Regulation Governing Implementation of Cremation Act, August 10, 1938, Art. 13

Each cremation chamber may accommodate only one body at a time. Prior to transferring the coffins into the crematory oven, each coffin shall be fitted with a heatproof plaque clearly engraved with the number of the cremation entered in the cremation register and the name of the crematorium. The ashes of each body shall be collected and placed, together with the plaque, in a durable, permanent, hermetically sealed container which shall be sealed by an authorized official. The cover of the container shall be furnished with a firmly attached permanent plaque, clearly and legibly engraved with the following information:

1. the cremation number, identical to the number in the cremation register and on the plaque enclosed with the ashes,

2. surname, first name and status of the deceased,

3. place, date and year of birth of the deceased,

4. place, date and year of death of the deceased,

5. place and date of cremation.